Intermittent problems are the ones that test you. Not because the failure is always complex, but because it refuses to show itself on demand. One minute the vehicle behaves perfectly. The next, it strands someone in a grocery store parking lot and then starts right back up as if nothing happened. For technicians, that kind of "now you see it, now you don't" behavior can lead to wasted hours, unnecessary parts replacement, and a customer who's losing faith in the car-and in everyone who has touched it.

This is a story about a connection that looked perfect, felt perfect, tested "good," and still caused a no-start condition. It's also a reminder that a clean connector with strong pin tension is not automatically a healthy connector-and that sometimes the problem is hiding where you're least likely to look.

The Complaint: A No-Start That Wouldn't Repeat on ScheduleA 2015 Dodge Dart came into the shop with an intermittent no-start complaint. The customer's description was specific enough to be frustrating: every two to three weeks, the car would randomly refuse to start. It didn't follow a pattern. Sometimes it happened cold in the morning. Other times it happened after running errands. And just when it seemed like the vehicle was headed for a tow, it would start again with no obvious reason.

Intermittent failures like this can quickly turn into a guessing game, but the Dart did give one clue. The only stored code was U0101 in the powertrain control module: lost communication with the transmission control module (TCM).

On paper, that's a solid lead. In practice, it can still be a trap.

I drove the car off and on for two days and couldn't get it to act up. No stall, no warning lights, no communication failures-nothing. It behaved like a perfectly normal Dodge Dart. That's often the worst case: the customer experiences a repeated failure, but the technician can't reproduce it, so the car looks healthy during testing, and the risk of misdiagnosis increases with every hour.

Then, finally, it happened.

The Day It Failed: No Crank and a Missing Shift IndicatorOne morning I went to pull the vehicle outside for the day and it had a no-crank condition. That's the moment every diagnostic tech waits for: the failure is active, and active failures tell the truth.

The first thing I noticed wasn't under the hood. It was the dash. The instrument cluster had no parking indicator lit-no "P," no gear position display, nothing. That detail mattered because on many vehicles the shift position data is necessary for enabling crank, and a missing gear indicator can mean the network is down, the module isn't powered, or the module isn't communicating.

I connected the scan tool. The results were revealing:

- No communication with the TCM

- Other modules were talking and communicating normally

The vehicle's network wasn't globally down. This looked isolated to the TCM-either the module itself had failed, the module had lost power or ground, or something in the connector/harness was interrupting communication.

The Rabbit Hole: "Just Replace the Module"I checked Alldata and Identifix. There were only a couple of confirmed fixes listed, and the theme was consistent: replace the transmission control module to resolve a no-start issue.

That's the kind of recommendation that sounds clean and efficient-until you notice the pattern in the real world. Too many vehicles have had expensive control modules installed as "confirmed fixes," only to come back with the same symptom because the real problem was a power feed, a ground, a network wire, or-most often-something in a connector.

Therefore, before I treated this as a "bad module" situation, I went to the wiring information and started verifying basics.

The Usual Checks: Power, Ground, and the Relay OutputAccording to the schematics, the TCM had the expected fuse protection and ground points. I checked the fuses, relays, and grounds feeding the TCM. Everything looked good.

On this vehicle, the relay that powers the TCM is integrated into the body control module (BCM). That can complicate things, but the BCM's 12-volt output to the TCM checked out.

Next step was physical access. The TCM is located on the passenger side, under the carpet. When I got eyes on it, I noticed something that immediately changed the tone of the diagnosis: salvage yard numbers written on the outside of the module.

That raised a bigger question: Is this really a module failure-or is this a car that's been through multiple "module fixes" because no one has found the actual cause?

I contacted the customer, and the history confirmed my suspicion. They told me the TCM had been replaced twice, along with the BCM, battery, and starter, all in an attempt to solve shifting complaints and no-start concerns. They'd been fighting the problem for over a year.

At that point I felt strongly that it wasn't likely the car had simply "eaten" multiple control modules. It was far more likely that something upstream was damaging communication or power-and that previous repairs had been chasing symptoms.

Signs of Previous Work: Tape, Tool Marks, and TamperingI began inspecting the harnesses and noticed fresh electrical tape, suggesting prior repairs or at least previous attempts to access wiring. At the TCM connector I could see pry marks, as if someone had previously disassembled the connector.

When I see evidence of connector tampering, I start thinking about pin fitment problems. If someone back-probed aggressively, forced oversized test leads, or tried to "tighten" pins the wrong way, pin tension can be compromised. That can cause intermittent opens that come and go with temperature and vibration.

I pulled out my pin drag tool and evaluated pin tension. Every pin had nice resistance-no loose terminals, no obvious spread pins. From the outside, the connector looked clean. No corrosion. No moisture. No green crust, no bent terminals, no broken locks.

Next, I did load testing. I used a load light and tested:

- TCM grounds, one at a time

- TCM power circuits

Everything carried load and lit the light brightly. No voltage drop red flags. No weak ground. No fading light when wiggling the connector-at least not yet.

At this stage, the evidence was pulling me toward the conclusion I didn't want; maybe the module really was faulty.

The Turning Point: The Wiggle Test Finally Tells the TruthI reassembled the car and it started right up. Communication returned, the cluster gear indicator displayed properly, and everything worked as designed.

I considered a heat-related failure and used a heat gun on the TCM. Even hot, it wouldn't act up. So, I went old-school. I started tapping components and performing the wiggle test-carefully and methodically-on every connector I could reach. I got the breakthrough.

When I grabbed the TCM harness and pulled, the shift indicator blanked out again and the car went into failsafe. That was the first time the failure reacted to my input, and that reaction was gold.

I repeated the test, pulling and tugging wire by wire, trying to isolate exactly which circuit was dropping out. At first, I couldn't find the specific wire causing it. I thought I had missed something during load testing, so I repeated the entire process again.

On the last power wire, the load light came on bright until I started to pull the terminal slightly and then the light went out.

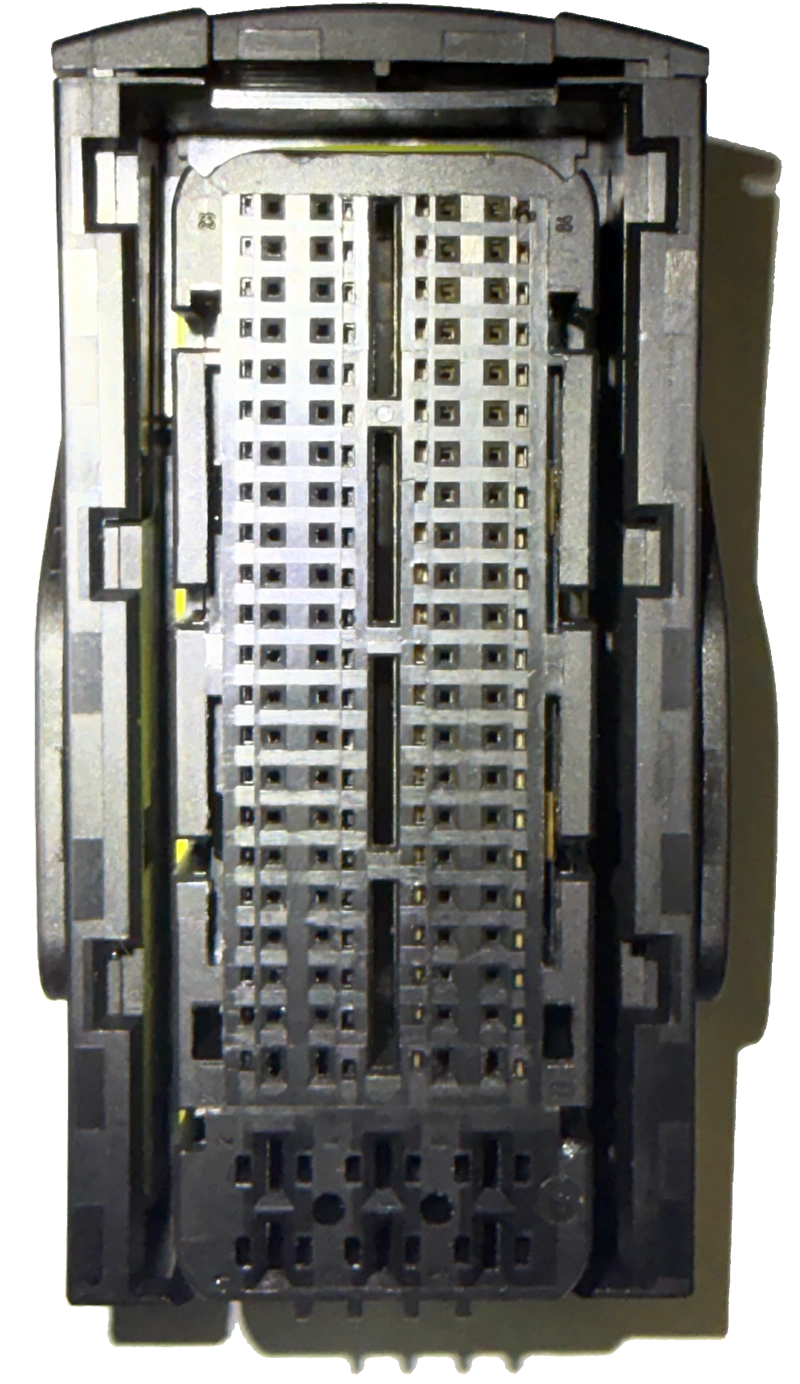

Here's the part that mattered: the connector was fully seated, locked, and looked fine. (Figure 1)

Figure 1

But if I pushed the pin in just slightly, the load light would illuminate. If I pulled it out slightly-even while still "connected" the light would go dark.

That behavior is the definition of an intermittent open: the circuit can test good, behave good, and then fail with the smallest change in position.

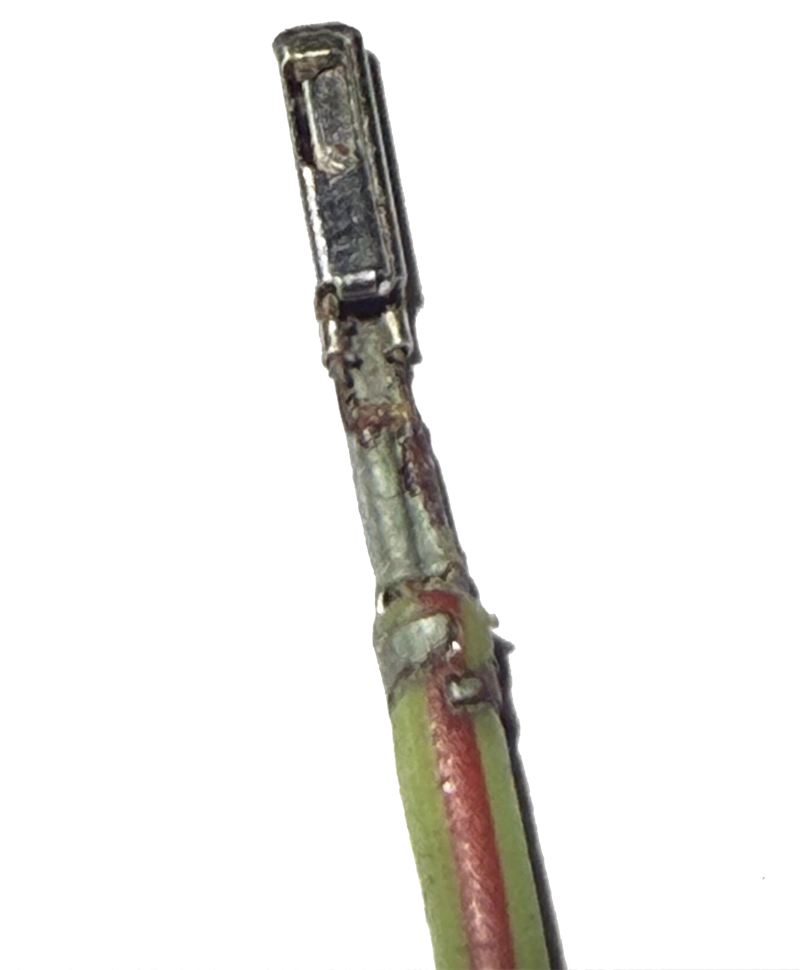

The Real Problem: Hidden Corrosion Inside a "Perfect" ConnectorNow I knew I had something real, so I disassembled the connector to get a direct visual on the terminal and its crimp connection.

That's when the truth showed itself.

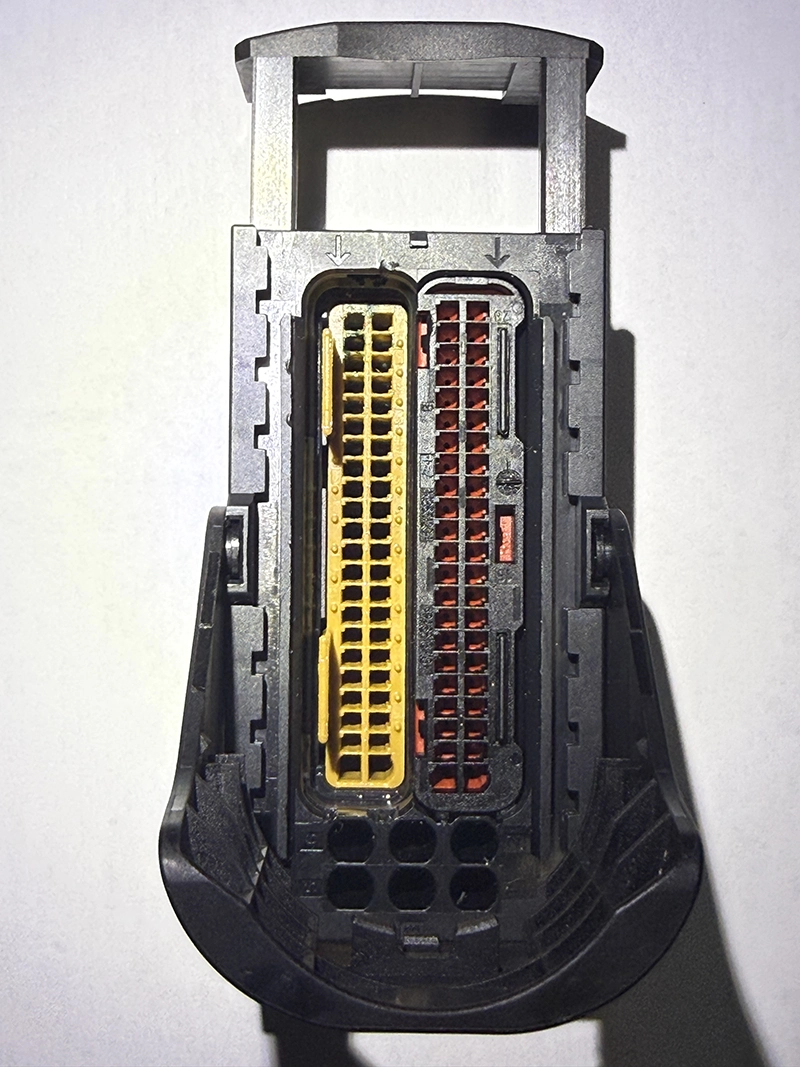

Inside the connector was a large amount of corrosion, concentrated where the terminal was crimped. Externally, it looked clean. The terminal fit felt solid. Pin tension was good. But internally, the conductor and terminal were corroded to the point that the connection could be pulled apart and broken, even though it looked normal from the outside. (Figures 2 & 3)

Figure 2

Figure 3

It was a nearly perfect diagnostic trap: a connector that passes quick inspection, resists the pin drag tool, and even carries load-until it's moved just enough to separate the compromised internal contact.

I was close to condemning the module. In a different situation-if the failure hadn't occurred in the shop, or if the wiggle test hadn't triggered it-it would have been easy to replace the TCM again and "hope" the problem went away for a while.

The Fix: Replace the Connector and Repair the Corroded WiresWe sourced a new connector, and I replaced the wires that showed evidence of corrosion. After the repair, communication stayed stable, the shift indicator functioned normally, and the vehicle has had no repeat issues since.

The customer's year-long battle ended not with another expensive module, but with a connector repair that addressed the real root cause.

The Takeaway: Clean and Tight Doesn't Mean HealthyThis case changed my habits.

I've seen plenty of connectors fail because they were visibly corroded, water damaged, loose, or broken. What I hadn't seen, at least not like this, was a connector that looked clean, had good pin tension, and still hid severe corrosion where it mattered most.

It makes me wonder what happened early in this car's history. If the first TCM replacement happened because of corrosion-related communication issues, it's possible someone cleaned the outside of the connector well enough to remove obvious evidence, while the internal corrosion remained. Over time, the compromised connection could easily create the same symptom again: intermittent network loss, missing gear indicator, failsafe behavior, and a no-start condition.

From now on, when the symptoms and history suggest module failure-but the pattern feels wrong-I won't stop at "connector looks clean." If I suspect a connector, I'll take it apart and inspect it internally, especially when the vehicle has a history of repeated module replacements.

Sometimes the worst connections are the ones that look like the best ones.

Certified Transmission

Certified Transmission